Discursive and Critical Design Practice

From the modernist perspective, design has been primarily regarded as a problem-solving practice, usually dealing with problems detected by other professions. In this sense, the mission of design is closely linked to the needs of the industry or, in a broader sense, the creation of a better living standard. From such modernist perspective, design is seen as a service activity that primarily addresses clients’ needs. However, as graphic designer and publicist Dejan Kršić points out, design has always been a signifying practice that generates, analyses, distributes, mediates and reproduces social meaning, especially nowadays, in the context of the new social, technological, media and economic conditions.

The relation between design and art (and other related disciplines) can be observed in several stages, i.e. from the high modernist synthesis of applied arts, visual arts and design in the 1950s, to the scientification of design throughout the 1960s and the emphasis on its rationality and the postmodernist position in which it is once again positioned at the centre of the interrelations of various disciplines, no longer through a complete synthesis, but, above all, through their interaction. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that an increasing number of designers take upon some new approaches to design. These “new designers” act on the borders of traditionally defined disciplines, removing the borders between them.

In their research, these new designers relate to diverse fields of science, primarily computer sciences and engineering, sociology, psychology, architecture, and, in the recent times, increasingly to biotechnology, all with the goal of critically reflecting on the development and role of technology in society. Designers re-think the role of technology in everyday life, without dealing with the applications of technology, but rather by considering its implications. Turning away from the commercial aspects of design with the focus on the demands of the market, they are now engaged with a broader social context. The new designers use design as a medium and focus on concepts and artefacts, and, rather than solving problems, ask questions and open issues to discussion.

The researcher and educator Ramia Mazé says there are three different approaches to critical design practice: the first sees designers reflecting on and critically questioning their own design practice; the second approach is based on a macro-perspective, re-thinking the design discipline as such; whereas in the third approach the design discourse is directed towards broader social and political phenomena. Mazé points out that these approaches are not mutually exclusive, as they most often intertwine and supplement each other in practice.

Historical references of critical design practice point to radical architecture of the 1960s, and partially to the critical practice of avant-garde and neo-avant-garde art. They are particularly inspired by the narrative quality and imaginary worlds of literature and film. Design and critical practice create more intense links in the interaction design, a specialized field of design that emerged in the early 1990s as a result of the accelerated development of digital technologies. The classical definition of interaction design describes it as a practice dealing with the ways in which people connect via the products and technologies they use, i.e. with the design of our everyday lives via digital artefacts. Today, it is most commonly associated with the design of digital products, applications or services.

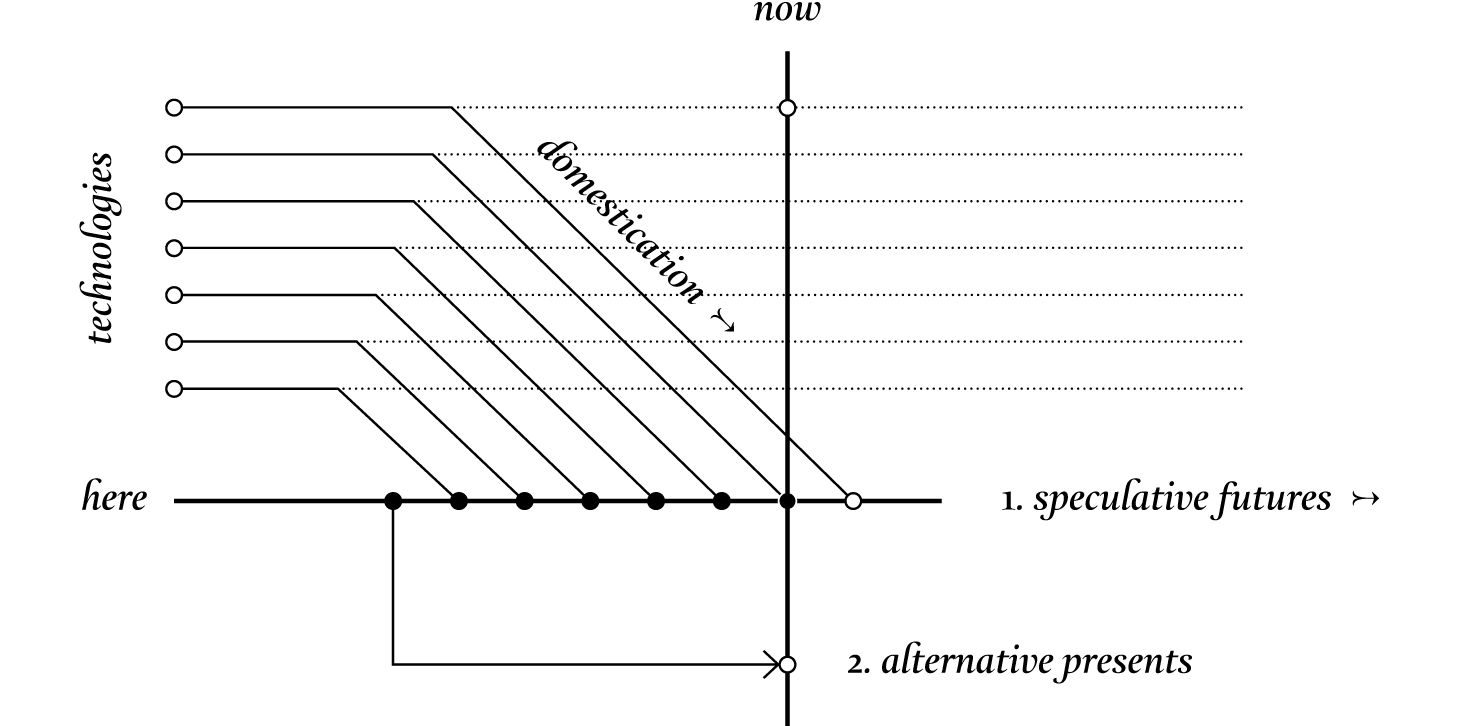

In this context, through his own personal design practice, and later through the establishment of a novel educational approach as the Head of the Design Interactions Department at the Royal College of Art (RCA) for many years, Anthony Dunne, in an approach he termed “critical design”, has dealt with the aesthetics of the use of new technologies in the context of electronic products. However, over the years, and in collaboration with Fiona Raby, he expanded the focus of his activities to the cultural, social and ethical implications of new technologies, and, most recently, on speculations about broader social, economic and political issues. Alternative presents and speculative futures (Auger). Here and now: everyday life and real products available on the market. The higher the line, the more emergent the technology and the longer and less predictable the transit to everyday life. Speculative futures exist as projections of the lineage in future. The alternative reality presents a shift from the lineage at some point in the past to re-imagine our technological present.

Speculating through Design: a question instead of an answer

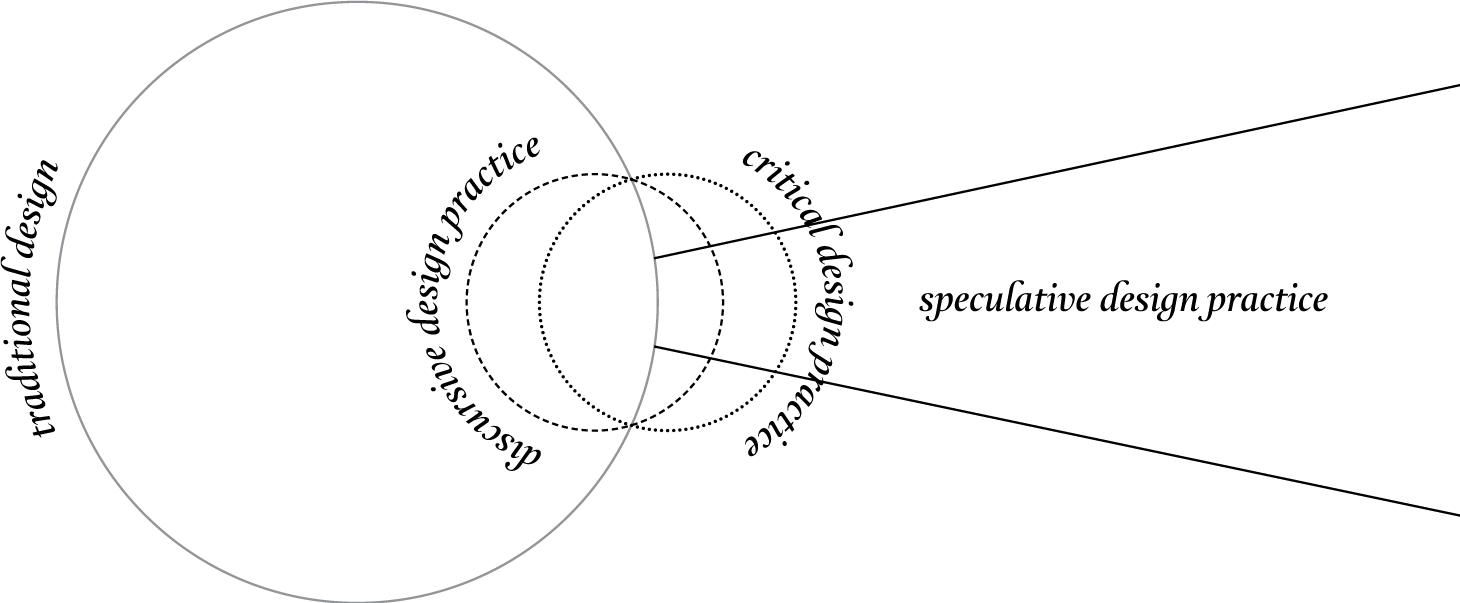

Speculative design is a critical design practice that comprises or is related to a series of similar practices known under the following names: critical design, design fiction, future design, anti-design, radical design, interrogative design, discursive design, adversarial design, futurescape, design art, transitional design etc. For instance, design fiction is a potential genre of speculative design practice, and “critical design”, as defined by Dunne, is a possible approach.

Speculative design is a discursive practice, based on critical thinking and dialogue, which questions the practice of design (and its modernist definition). However, the speculative design approach takes the critical practice one step further, towards imagination and visions of possible scenarios. Speculative design is also one of the most representative examples of the new interaction between various disciplines. It is therefore interesting to see how new designers view their practice: they call themselves trans-disciplinary, post-disciplinary or even post-designers, quite often even simply – designers. Sometimes they do not even declare to be acting from the design perspective at all.

By speculating, designers re-think alternative products, systems and worlds. Designer and teacher at the RCA, James Auger, says that this design (i) moves away from the constraints of the commercial practice (steered by the market); (ii) uses fiction and speculates on future products, services, systems and worlds, thus reflectively examining the role and impact of new technologies on everyday life; (iii) and initiates dialogue between experts (scientists, engineers and designers) and users of new technologies (the audience).

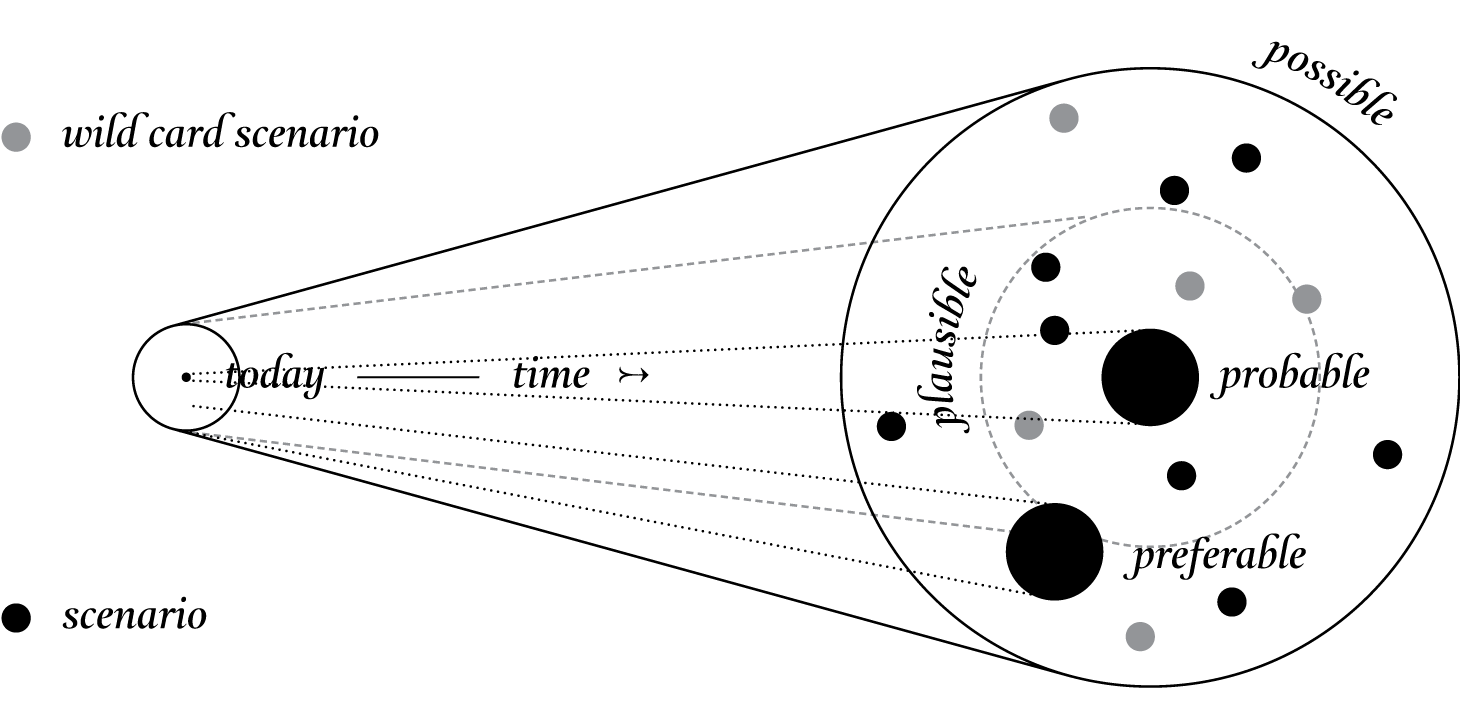

Today we can see that capital uses promotion and investments in the technology by programming the technological development to actually colonialize the future. In this technological context, design often acts in the so-called “Western melancholy” discourse where “the problem” of technological alienation, manifested as the extinction of real social interactions, “is resolved” with the production of new technologies or new products as an intention to once again instigate long gone social interaction. And, whereas traditional design actually legitimizes the status quo, speculative design envisages and anticipates the future, at the same time help- ing us to understand and re-think the world of today. This approach is most often based on the question “what if?”, examining the interrelation between potential changes in the technological development and social relations. Rather than engaging only with a future that we desire, this approach also deals with the future we fear might come true if we fail to critically consider the role of new technologies in the society.

Such an approach to design does not focus on meeting the current and future consumer needs, but rather on re-thinking the technological future that reflects the complexity of today’s world. Speculative practice opens space for discussing and considering alternative possibilities and options, and imagining and redefining our relation to reality itself. Through its imagination and radical approach, by using design as a medium, it propels thinking, raises awareness, questions, provokes action, opens discussions, and can offer alternatives that are necessary in the today’s world.

Speculative design fictions find their inspiration in science fiction, which has a long history of creating imaginary scenarios, worlds and characters with which audiences become closely identified. Imaginary worlds are an exceptional source of inspiration to designers in their re-thinking of the future. However, such approaches to speculative fiction, as conceptualized, for instance, by the science fiction author and futurist Bruce Sterling, are often part of the technological paradigm, and, as such, reaffirm the technological progress instead of questioning or being critical of it. By the creation of imaginary worlds, and by designing fictions, we actually question the world we live in its values, functions, its metabolism, as well as the expectations of its inhabitants.

Ramia Mazé underlines that design practices can never be neutral there are always critical and political issues, as well as alternatives and futures linked to them. Thus, Dunne and Raby emphasize the potential of speculative design for large-scale social and political issues, such as democracy or sustainability or the alternatives to the existing capitalist model. In this context, publicist and activist Naomi Klein warns that the present domination of dystopian scenarios in literature and films leads to a view where catastrophic scenarios are unavoidable, which results in making us passive rather than proactive. It should be kept in mind, therefore, that the purpose of speculative design fictions should not be utopian or dystopian science fiction visions of the future, but dialogue on what the future can be.

For instance, with its explicit focus on the future, the speculative design approach offers a stimulative framework for re-thinking visions of networked cities of the future. Liam Young, a speculative architect who says that his work lies in “a space between design,fiction and future”, sees speculative fictional cities of the future as a starting point for debate and discussion, scenarios that we will love or hate, which will “not just anticipate, but actively shape technological futures through their effects on collective imagination”. He points out that “cast as a provocateur and storyteller, the speculative architect instigates debate, raises questions and involves the public as active agents in the future of their cities, and brings us closer to the technologies that are increasingly shaping the urban realm and the scientific research that is radically changing our world”. However, speculative design can also function in the so-called “real world”, i.e. in companies employing designers to consider scenarios for future trends and research into the adoption of emerging technologies.

Methodology?

Although the speculative approach to design can primarily be seen as an attitude or position rather than a traditionally defined methodology, especially since many designers practice the approach without using this term, we can still point out some distinctive characteristic of the approach and determine a basic framework. Since speculative design continuously interacts with other related practices, fields and disciplines, it uses any methodology that is accessible and appropriate at any given moment. For instance, it legitimately uses tools, techniques, instruments, methods, genres and concepts such as fictional narratives, film language, screenplay, storyboard, user testing, interviews/questionnaires, games, but also media and pop culture phenomena, such as candid camera, elevator pitch, observational comedy, stand-up, etc. Anything considered suitable at a given moment is legitimate.

Design is based on the observation and understanding of the world around us, and by practicing it we endeavour to articulate our needs, desires and expectations. The problem arises when we want to expand the horizon of our observation in order to identify emergent themes. The question is how to begin with the design of concepts when we do not know what the design space itself will look like, let alone who its users will be. The approach and practice of speculative design is a particularly stimulative strategy for researching the “space” that lies beyond “current”and the“now”.

Speculative practice may seem as a top-down approach at first glance, placing the designer at the centre of the process, offering her personal vision, without involving the target audience. However, let’s keep in mind that one of the main goals of speculation is the inclusion of the public in the re-thinking and dialogue on new technological realities and new social relations. Also, a successful speculative project is necessarily connected to the research of a social context, and is fundamentally directed towards the individual needs and desires.

The practice demonstrates that the speculative approach has potential in multidisciplinary teams, where it initiates dialogue and generates a context in which the participants can simultaneously re-ex-amine the boundaries of their disciplines and discover links with other disciplines. The process can be split in a few steps: the first one implies critical design research to define a design space. After this, speculative concepts and ideas are generated and further developed to finally articulate forms which are suitable for communication.

The speculative approach frequently uses methods of contemporary art. However, as opposed to general artistic practice, design uses a language recognizable to a wider audience, and is not confined only to galleries and salons. Publicist and critic Rick Poynor points out that, contrary to artistic practices, design is not declared an artistic fantasy out of hand, and ignored by companies, institutions and policymakers. Design is also in close contact with the new technologies and consumer society, popular media and pop culture, which is why today it boasts a significant media and social impact. Pop-culture forms, through novels, films, computer games and so on, often seem to be better platforms for speculative projects than galleries and museums (actually, that is a natural environment for design).

Speculative practice is related to two basic concepts: speculation on possible futures and the design of an alternative present. Speculation on the future generates scenarios of the future that critically question the concept of development, the implementation and use of new technolo gies and their wider social implications. The concept of an alternative present refers to the creation of parallel urban technological realities. These specific approaches offer a rich narrative potential for the questioning and criticism of technological development, but also of contemporary society as such. The issues dealt with can be exceptionally broad, from big socio-political topics to ordinary everyday activities.

Speculative fictions do not exist solely in a futurist vacuum, because the past (i.e. the present we live in) fundamentally impacts our designed vision of the future. As opposed to the open form of science fiction, in speculative fiction there is a link between the present and the imaginary future. Therefore, when re-thinking the future we must think about technologies and social relations that can emerge from the current world we live in. We must bring into question the assumptions and prejudice we have about the role of products and services in everyday life. The extension of the everyday into the future is what makes speculative design fiction powerful and profoundly intriguing.

Dunne emphasizes that these design processes primarily deal with designing relations, rather than objects themselves. This is why speculative design can, as a result of such processes, offer new speculative products and services, even new social and political systems (worlds). However, the success and impact of a speculative approach, as perceived by the target audience, primarily depends on the believability of the designed artefacts and potential scenarios of the future. The concepts materialize and communicate in the form of narrative or documentary video and film fictions, fictional products (prototypes), software applications, instructional videos, user manuals, graphs/diagrams, TV news reports, fashion accessories, etc. The socalled “diegetic prototypes” originate in cinematography where they exist as fictional but entirely functional objects whereas in speculative scenarios they serve to create the suspension of disbelief about change.

Speculative practice draws inspiration from the poetics of literature, music, visual arts, film, computer graphics and architecture, especially in their avant-garde forms. Storytelling has considerable power and a deep-running tradition in human history in stimulating discussions and critical thinking. Speculative scenarios are open-ended and offer the audience the possibility of personal interpretation. They frequently include humour, often of the dark variety, close to satire, which activates the audience on an emotional and intellectual level, in a way similar to literature and film. Speculative scenarios are often unusual, curious, occasionally even disturbing, but desirable and attractive to the audience. However, only concepts that successfully communicate with the suspension of disbelief, actually provoke attention, emotions, and stimulate thinking and discussion, which, after all, is the main goal of speculative practice.

Design Practice for the 21st Century or a New Utopia?

The basic reference of the speculative (and critical) design practice is primarily the radical Italian architecture and design practice in the 1960s and 1970s. The founding principles of the radical approach, resistance to the mainstream modernist practice and technological domination, focus on social topics, re-thinking of the profession, very often through a political prism as well, today figure as the main characteristics of speculative and critical practices. The context of exceptional technological progress and domination at the time when radical practices emerged may be related to the present technological context (nano and biotechnologies, data-rich urban environment, ubiquitous computing and so on). And as the radical design was challenging or putting in question the modernist paradigm as the dominant ideology of the time, the new (speculative) design practices are confronting the dominant consumerist ideology. However, it remains to be seen whether the speculative practice has the potential to become the new, post-design practice, “design after design” or yet another utopia and historical reference.

Those who criticize the currently dominant approach to the speculative practice, characterised as “Eurocentric”, highlight its excessively focus on aesthetics (on the visual and narrative level), tendency to escape to dystopian scenarios, vanity and separation from the real world. Cameron Tonkinwise, Head of Design Studies at the School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University, underlines that many dystopian scenarios found in present-day speculative fictions (of the Western world) actually (and unfortunately) have been already taking place in other parts of the world. He also highlights that the present role of speculative design should provide solutions for mistakes of the modernist project and re-materialize in our everyday lives the visions of a radically different future. In an online discussion on the occasion of the exhibition Design and Violence showcased at the MoMA, the critics of this “Eurocentric” approach point out the privileged “Western” position stating that criticism is only possible outside of this comfort zone, by taking a position and organizing activities in the “real world”.

In order to expand the exhibition, we tried to answer the question through a series of interviews with the authors of the presented works together with the prominent international practitioners in the filed of speculative design. We have also incorporated a discoursive view of the eminent experts in the field of speculative (and general contemporary) design practice.